© The Trustees of the British Museum. Used under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0.

As we prepare our map of historic army barracks, we have had to make decisions about what barracks to include and exclude. In some cases, we have made a decision to leave out a building or complex because it was never used as a regular army barracks or was only used on a temporary basis. In the former case, it might be that it was built for fencibles, yeomanry or the militia – all part-time or voluntary non-regular military units.

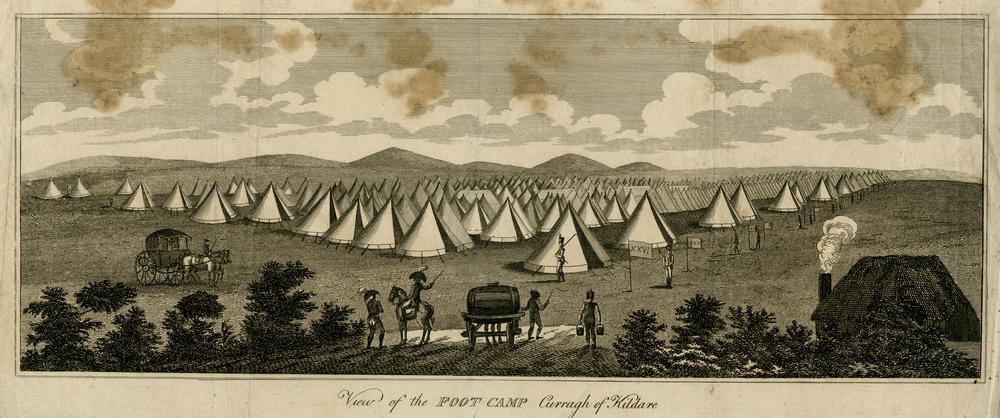

In the latter case, there were many temporary barracks put in to use at times of war or other security crises, but which were never permanent residential military complexes. These included private buildings converted to military use for a short period of time, or temporary installations such as hutments and camps – these could be quite substantial, sturdy and lasting complexes of structures, but they were never intended to be permanent. Hence, while from the late 1690s onwards there were usually somewhere between 50 and 100 permanent barracks in use throughout Ireland at any one time, heightened security crises or war could see the military’s official listings of barracks grow dramatically with the addition of many, many more locations.

A good example comes from an 1801 listing, towards the end of the French Revolutionary Wars and following the 1798 rebellion, which comprises almost 400 locations around Ireland in which soldiers were stationed. These included the placement of units at sixteen locations along what was called the ‘canal-line’, as a means of securing the strategically important grand canal in case of invasion or further insurrection. The unit strengths ranged from two officers and ten men at Burgh’s Bridge to eight officers and 300 men at Sallins.

In Dublin, soldiers were stationed in a whole range of different temporary locations including 344 men at numbers 1, 2, and 3 Sackville Street (their thirteen officers were housed in numbers 14 and 42 on the same street) as well as in Jervis Street, Mary Street, Abbey Street, Henry Street, Essex Street, Camden Street, Cork Street, the Coombe, and Dolphins Barn. In total, there were 251 officers and 5,260 men in Dublin at that time. Such temporary locations at different times included schools, jails, courthouses and other government-owned properties. As for the other species of military residential complexes – hutments and camps – that is another day’s story.